Sustainable Education: New Visions for Teaching in the Field

The McMaster archaeological field school, directed by Dr. Scott Martin, has created a lot of buzz here at Sustainable Archaeology, and it has got us thinking about current approaches to teaching and learning in the field and how they relate to our goals for collections management and research in Ontario.

Jun 06, 2016

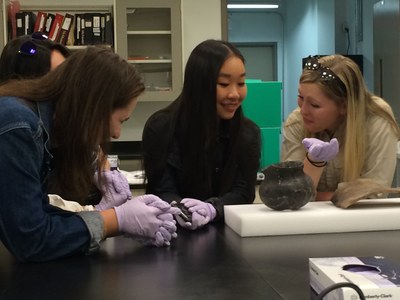

A couple weeks ago, the students put down their trowels and came to visit us for a tour and the opportunity to look at artifacts from previous excavations at the same site, in addition to other sites in the area. From the nitty gritty of storage and conservation to petrography and soil analysis, the students got a good taste of what we do, day to day. We also pulled out 3D printed models (printed at our sister facility Sustainable Archaeology Western) and discussed technology and digital platforms for archaeological collections management.

We later returned the visit, breaking from the confines of the basement here at SA, donning field boots that haven’t been muddied in far too long, and traipsed down to the shoreline of the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG). Dr. Martin obliged us with a brilliant tour of the site and the progress they had made.

If you have had the chance to visit the RBG before, you know what a magical setting this is. From old growth trees to marshlands to the open waters of Cootes Paradise, the place is alive with birdsong, chipmunks running underfoot, and habitual glimpses of turtles, raccoons and snakes. Tucked away just inside a rusting fence, and surrounded by irises, lilac trees, and other dense foliage, the field school students have been exploring a long history of human activity in the area.

I will leave their archaeological discoveries to the research report that is sure to follow this field season, but it occurred to me while I was standing in the middle of a series of 1x1m units that the last time the field school ran (in 2012, co-directed by Dr. Meghan Burchell and myself, Katherine Cook), Sustainable Archaeology was in its infancy. We were concerned with ensuring that students left the field school with all the skills and understanding to be not just competent field archaeologists, but also responsible, ethical and innovative researchers and designed the course with those goals in mind. When the field school ended, the students were eager to help move the first collections and boxes into the empty shell that was the repository, recognizing the importance of that moment. When it came time to hire research assistants that fall, we returned to those same field school students, with whom we had had so many engaging discussions of sustainable practice, non-destructive techniques, and heritage management during the summer.

Fast forward four years, how has the focus of the field school and experiential education continued to evolve? Trying not to distract the students too much, I did pick their brains a bit while helping to screen dirt. They have certainly learned a lot more than how to hold a trowel or push dirt through a screen:

- ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE COMMUNITY: Located just off a path that is connected to a number of busy trail networks in the area, they have had frequent passersby in the form of hikers, school groups and other folks from the community. The students have learned a lot about talking to people, telling them about their findings, but also listening and hearing visitors’ stories about the landscape and the history of the site.

- ARCHAEOLOGY’S LEGACY: Although the Nursery Site is far from the most densely-packed site when it comes to finds, a lot of the students were already reflecting on the ways that the site had changed their perceptions of what it is to do archaeology, and how a site like this fits into narratives, heritage and understanding of the past, as well as popular (mis)conceptions about archaeology and the impact of media (in light of recent events). They were also uncovering the history of archaeology on the site and reflecting on the impact of field research on the landscape.

- THE FULL SPECTRUM: Whether in the field, the lab or on a field trip (SA, Six Nations, etc.), the students have fully participated in the spectrum that encompasses archaeological research. From uncovering an artifact in the ground, to seeing the vast repository of collections here at Sustainable Archaeology, the long, complex process of archaeology has left its impression. But the impression is one that reflects the responsibility and challenges of this discipline today, and the need to do better when it comes to alternative voices, access to knowledge and collections, and collaboration.

Having been following the progress of other Canadian archaeological field schools on social media, there is a widespread movement to update how we teach students about archaeology, and in particular inspire them to build a sustainable future for the discipline. The Western University and Museum of Ontario Archaeology’s Lawson Site “Un”Field School (directed by Dr. Neal Ferris), as it has dubbed itself, highlights that in undertaking “field investigations that are designed to protect the heritage value of this important archaeological site while remaining consistent with our aim to preserve the site.” Students learn valuable lessons in heritage management plans, public service, and alternative ways of doing archaeology.

These efforts are book ended coast to coast by further field schools that have moved beyond digging, from the west coast’s University of Victoria field school (directed by Dr. Erin McGuire) surveying a local Jewish cemetery, focussing on alternative narratives of history and public engagement (including a insightful blog written by the students, and even efforts on Snap Chat), to the east coast’s Memorial University of Newfoundland’s field school (directed by Dr. Catherine Loisier) that has included non-destructive analysis of historic sites, including GPR and intensive recording of an at-risk burial ground.

More broadly, efforts to approach heritage in universities’ own backyards is visible in the long-running and highly successful Campus Archaeology program at Michigan State University that combines education, engagement and research. Across the pond, a heritage field school (directed by Dr. Sara Perry, a Canadian ex-pat!), which runs alongside more traditional field excavations at the University of York, has students designing and crafting real-world heritage resources. This year they created an audio guide to the Breary Banks site (excavated by the historical archaeology field school, directed by Dr. Jonathan Finch). The students also maintained a thrilling blog that outlined all the steps to creating an audio guide, as a reference for others to follow. Last year, an app was created that led visitors through the landscape of Breary Banks. Numerous other examples from around the world highlight the clear focus to provide archaeology students more than basic excavation skills training, including empowerment, collaboration, and engagement.

We are optimistic that these changes, both local and abroad, reflect a growing value placed on sustainability, access, and ethics by archaeologists today, but also a hint at the skills, experiences and principles that the next generations of archaeologists will bring to the table.

Article by Katherine Cook, Operations Manager